I’m reminded of the character Vizzini (played brilliantly by Wallace Shawn) in the movie The Princess Bride – who keeps using the word inconceivable. Finally, the character Inigo Montoya (played with equal brilliance by Mandy Patinkin) says:

You keep using that word. I do not think it means what you think it means.

It’s definitely conceivable that we’re seeing something similar with the use of the word disruption in healthcare. It’s embedded in the title of several books (by noted authors) and countless headlines through the years (now including this one). But like the character of Inigo Montoya – I’ve come to believe the word doesn’t mean what we think it means – for 3 really big reasons.

Training

Healthcare is one of the most expensive industries ever devised. By far the largest and most expensive portion of this industry (in terms of actual delivery) is an expensive service. The motivation, of course, has largely been born out of compassion to reduce pain and suffering – but let’s not kid ourselves either. Often the motives are simply big bucks greed. Here in the U.S., the greed part is fueled by a very simple free market equation: Demand (by patients) will always outstrip supply (of doctors). Always.

It takes about 10 years to train a doc. At graduation, the average medical student debt is about $160,000 (sometimes a lot higher). If you’re one of those fortunate graduates – you’re looking at how to pay back what amounts to a home mortgage – in the fastest time possible. Here are your options based on the average annual compensation by specialty.

Now, would you like that mortgage paid off in 10 years – or 5? Independent of any noble motivation to “practice medicine,” these are the very real economics within the profession of healthcare. We can change this, of course, but then we better look hard at the cost/benefit equation of medical training. What we have today supports sickcare – not healthcare. [Footnote: French docs graduate with $0 debt]

Demand Distribution

Much of the interest, focus, and attention around disrupting healthcare today continues to be on the low-acuity, primary and preventative sides of the system. That’s logical because it’s often at the entrance of the healthcare system and if you can’t (or won’t) change the supply chain – maybe you can have an impact on the demand side.

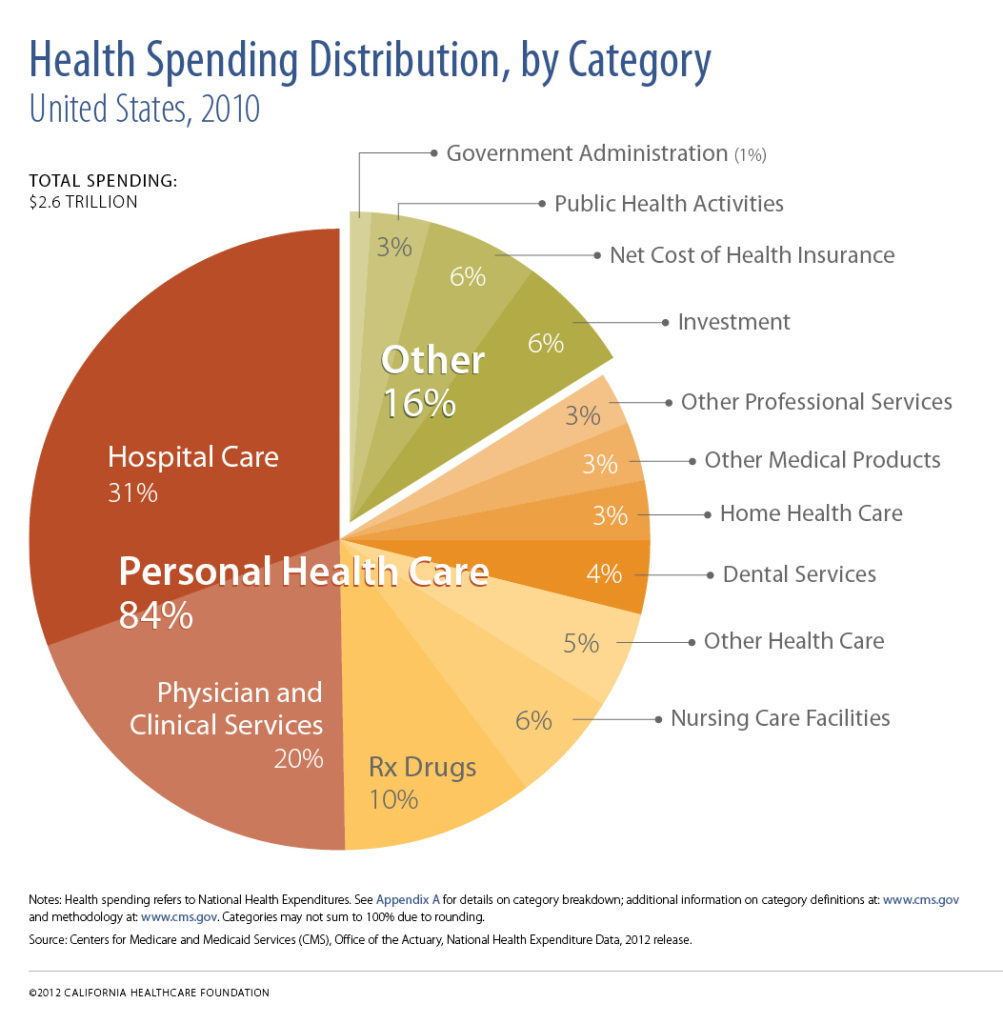

The problem is – that’s not where the big healthcare expenses are – and it doesn’t fundamentally change the system. We’ve also lost a fair amount of time (through the years) chasing the wrong bad guys – the insurance companies – which we conveniently blamed for much of the medical gluttony for the entire industry. Just like low-acuity healthcare – that’s not where the big dollars are being spent (and it’s certainly not where the big net profits are). Here’s the category breakdown of our National Healthcare Expenditure for 2010 (CMS data as published by the California Healthcare Foundation in 2012):

The net cost of health insurance is 6%. Nothing to sneeze at to be sure, but if you’re trying to “disrupt” a system that’s running at $3.5T per year (about 18% of GDP) is that really the best place to start? Just asking.

Startups Aren’t A Good Source For Disruption

Last month, Francisco Dao wrote a brilliant piece he called “Why Startups Rarely Change the World.” What he said applies with equal strength to every sector – but perhaps more so to one that is almost entirely based on really (really) expensive services – healthcare.

… changing the world almost always requires massive amounts of money, groundbreaking technology, and a lot of time — three things most startups don’t have.”

Really big paradigm shifting developments are so costly and require such a long term outlook that they essentially have to be disconnected from the profit requirement. As such, the only people who can afford to do this kind of work are the research labs of big companies (think Bell Labs in the old days and Google today) and the government. Even startups that raise massive VC rounds don’t have resources anywhere close to what Google or the government can provide.

For those of you sharpening your anti-government pitchforks, where do you think the Internet came from? The government funded this experiment for decades without any expectation of profit and gave it to private industry for the rest of us to make money with. Everything we’ve done since then, from Amazon to underwear delivery, stands on the shoulders of profitless government funded research. Creating the Internet was the fundamental development that changed the world, not mailing crap in a box.

That’s not to say there won’t be spectacular successes – with big valuations, big exits, and windfall profits – but the real question remains. Are they truly disruptive at the core – or just around the edges?

Contrary to many who say our healthcare system is broken – it really isn’t. It is performing as it was designed. The people in it aren’t to blame – and we can absolutely change it – but we have to really want that change. That kind of change is at the core of the system – with different goals, objectives, and outcomes in mind. That’s much less of a technology problem and much more of process improvement one. Technology can – and will help – but all too often it’s a tactical overlay to try and patch the flawed system we’re living with today.

Unfortunately, this kind of change (dare I say disruption?) isn’t one that startups can deliver – and nor should we expect it from them. Just like startups, however, the kind of change we desperately need also has a big source of available capital. It just has a different street address. It’s not Sand Hill Road – it’s K Street. In terms of any attempt at comparison – it’s the difference between grind play on the slot machine (where many can and regularly do hit million dollar jackpots) and the private rooms of Baccarat for the whales that are flown in from around the world on private jets. As long as the whales are having fun – the casino (and slot machines) will remain open. Any way you look at that – it’s not disruption.

This article first appeared in Forbes (September 2013)