Earlier this year, Cadillac ran a controversial TV ad that first aired during the opening ceremonies of the 2014 Winter Olympics. It was called “Poolside” and featured actor Neal McDonough extolling America’s work ethic over other countries — specifically France.

Turns out that many of those “other countries” (including France) score better than the U.S. in one key metric not included in Cadillac’s TV spot — healthcare. At least that’s according to The Commonwealth Fund in their latest report “Mirror, Mirror On The Wall — 2014 Update” (pdf here).

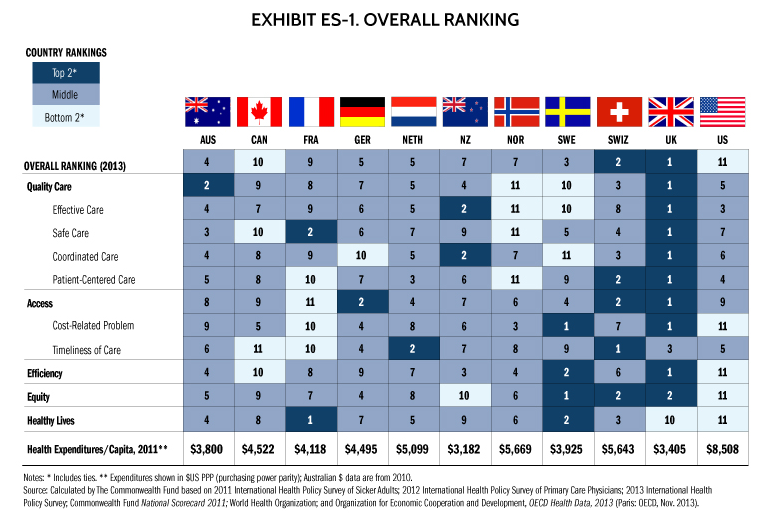

For this year’s survey on overall health care, The Commonwealth Fund ranked the U.S. dead last.

1 – United Kingdom

2 – Switzerland

3 – Sweden

4 – Australia

5 – Germany & Netherlands (tied)

7 – New Zealand & Norway (tied)

9 – France

10 – Canada

11 – United States

It’s fairly well accepted that the U.S. is the most expensive healthcare system in the world, but many continue to falsely assume that we pay more for healthcare because we get better health (or better health outcomes). The evidence, however, clearly doesn’t support that view.

The report itself is fairly short (32 pages), but included prior surveys and national health system scorecards as well as data from the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). The report also included a list of major findings — including these:

Quality: The indicators of quality were grouped into four categories: effective care, safe care, coordinated care, and patient-centered care. Compared with the other 10 countries, the U.S. fares best on provision and receipt of preventive and patient-centered care.

Access: Not surprisingly — given the absence of universal coverage — people in the U.S. go without needed health care because of cost more often than people do in the other countries.

Efficiency: On indicators of efficiency, the U.S. ranks last among the 11 countries, with the U.K. and Sweden ranking first and second, respectively. The U.S. has poor performance on measures of national health expenditures and administrative costs as well as on measures of administrative hassles, avoidable emergency room use, and duplicative medical testing.

Equity: The U.S. ranks a clear last on measures of equity. Americans with below-average incomes were much more likely than their counterparts in other countries to report not visiting a physician when sick; not getting a recommended test, treatment, or follow-up care; or not filling a prescription or skipping doses when needed because of costs. On each of these indicators, one-third or more lower-income adults in the U.S. said they went without needed care because of costs in the past year.

Healthy lives: The U.S. ranks last overall with poor scores on all three indicators of healthy lives — mortality amenable to medical care, infant mortality, and healthy life expectancy at age 60. Overall, France, Sweden, and Switzerland rank highest on healthy lives.

Perhaps the biggest single takeaway was this one:

The most notable way the U.S. differs from other industrialized countries is the absence of universal health insurance coverage. Other nations ensure the accessibility of care through universal health systems and through better ties between patients and the physician practices that serve as their medical homes. Mirror, Mirror On The Wall — 2014 Update

Unfortunately, many still equate “universal healthcare” with “Government run” or “single payer” healthcare. It isn’t (Universal Coverage Is Not “Single Payer” Healthcare — here).

All of which makes Cadillac’s advertising chutzpah even more brazen. After all, it was just seven short months ago that the Government “bailout” of GM officially ended. One of the more commonly cited reasons for the dire financial predicament of the auto industry giant was always — yup — ballooning healthcare costs. Just as Starbucks spends more on healthcare benefits than coffee beans — GM (at least in 2005) spent more on healthcare benefits than steel.

The U.S. excels in many areas, but clearly, population health (and all its related components) isn’t one of them. N’est-ce pas?

This article first appeared in Forbes (June 2014)