The lack of data interoperability in healthcare continues to plague and haunt the entire industry. Much of the challenge falls squarely in the realm of Electronic Health Record (EHR) software, but EHR software is by no means the only category where this challenge is directly affecting patient lives. I ‒ along with countless others ‒ have written extensively about this topic. Last year I did a 5‒part series on just ‘interoperability’ which I published on Forbes. One piece highlighted the importance and direct effect of lack of interoperability from the patient perspective: The View of Digital Health From an ‘Engaged Patient’

I wish I could say things have improved since ‒ they really haven’t ‒ nor are they likely to improve soon. We remain stuck in competing commercial interests, political agendas and very real technical challenges on how to securely share even the most basic health information. While the debate and agendas continues ‒ this year alone has seen the health data breach of 91 million Americans through just 2 high‒profile cases ‒ Anthem and Premera ‒ and that was just in the first quarter. Whatever the privacy argument is against sharing data ‒ it’s all but irrelevant when more than 90 million Americans have their health data breached. That’s effectively 28% of the U.S. population.

The result of all this is sadly theatrical ‒ a kind of Kabuki dance ‒ and reflects the broader inability of many to grasp the true meaning of “patient‒centered” thinking. It’s excruciatingly painful to watch ‒ let alone live through as patients.

The topic of ‘interoperability’ kept percolating throughout last year and finally reached the hallowed halls of Congress. Outraged that the Government had spent almost $30 billion dollars on “infrastructure” software that locked data in proprietary silos, the Government demanded some accountability through the Office of the National Coordinator (ONC). That report was delivered by ONC to Congress on Friday with this odd ‒ uniquely Government title. Report on Health Information Blocking

Pardon my French, but what the hell is ‘information blocking?’ As a software engineer, I’ve been around software most of my professional career and I had never heard that phrase before ‒ let alone as applied to software interoperability. Sadder still, it also highlights a real naiveté by ONC and Congress on the actual business of software manufacturing. If it’s not naiveté it’s certainly very theatrical.

The report itself is about 39 pages (including 6 pages of appendixes). It’s a painful attempt at laying blame for the lack of interoperability on the big, bad Independent Software Vendors (ISV’s). Even the first hurdle ‒ to define “information blocking” ‒ is an enormous challenge because it attempts to fabricate a definition from thin air. The report does acknowledge the scale and scope of this enormous difficulty outright.

The term ‘information blocking’ presents significant definitional challenges. Many actions that prevent information from being exchanged may be inadvertent, resulting primarily from economic, technological, and practical challenges that have long prevented widespread and effective information sharing. Further, even conscious decisions that prevent information exchange may be motivated by and advance important interests, such as protecting patient safety, that further the potential to improve health and health care. Finally, it is important to acknowledge that certain constraints on the exchange of electronic health information are appropriate and necessary to comply with state and federal privacy laws; this is not considered information blocking.

Undaunted by these challenges, ONC went ahead and fabricated a definition anyway.

Information blocking occurs when persons or entities knowingly and unreasonably interfere with the exchange or use of electronic health information.

With this broadest of definitions, I asked two healthcare legal minds I know for clarification on that gaping hole of a legal phrase called ‘unreasonable.’

Can U define “unreasonable” in @ONC_HealthIT “info blocking” report 2 Congress? http://t.co/ij20SPcjnX cc: @VinceKuraitis @healthblawg — Dan Munro (@danmunro) April 10, 2015

I fully expected the reply.

.@danmunro Agree, ONC language re: “knowingly & unreasonably” is unnecessarily high burden of proof. @ONC_HealthIT @healthblawg — Vince Kuraitis (@VinceKuraitis) April 10, 2015

It’s not just unnecessarily high. Given all the challenges listed outright by ONC ‒ it’s virtually impossible to prove ‘knowingly and unreasonably.’ Assuming you could even level the charge ‒ who would adjudicate the case ‒ and the resulting appeal ‒ at what cost ‒ and to whom? ONC knows this ‒ and acknowledged it indirectly further in their report.

ONC-ACB surveillance activities and other feedback from the field show that although certified health IT is often conformant with the criteria to which it was certified, there is still a substantial amount of permissible variability in the underlying required standards, unique clinical workflow implementations, and numerous types of interfaces to connect multiple systems. This variability has contributed to information sharing challenges and also creates opportunities for developers or health IT implementers to erect unnecessary technical barriers to interoperability and electronic health information exchange.

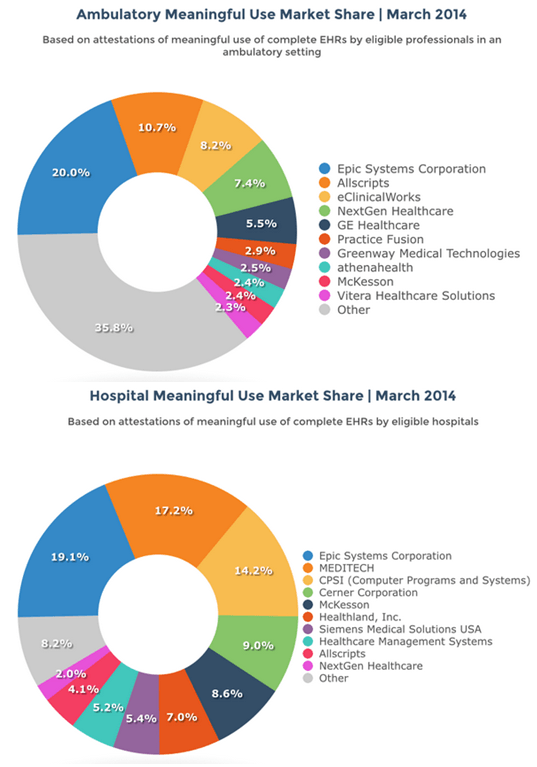

Commercial software ‒ specific to the healthcare industry ‒ has taken years to mature and there are distinctly separate categories of EHR software. Two of the largest categories are Ambulatory and Inpatient. One could argue that the first and most successful vendor in this unique category of software called EHR is Epic Systems ‒ founded by Judy Faulkner (1979) and still privately held. Here’s a relatively recent breakdown of market share ‒ by vendor ‒ for both categories.

With a firm hold on 20% of both markets, Epic is the Apple (or Microsoft) of EHR software except that it remains privately held. Whether a software manufacturer is privately held ‒ or traded on the public market ‒ makes little difference to the way the business operates. The reality is that most of these EHR systems started (and largely remain) as enterprise billing engines ‒ that now include a fair amount of clinical data ‒ stored in proprietary formats. Anyone ‒ including ONC ‒ who argues that Independent Software Vendors (ISV’s) are obligated to build software connections (or API’s) into competing software solutions ‒ for free ‒ clearly don’t understand the way revenue is captured and reported to the IRS. They also don’t understand that ISV’s are beholden to shareholders as much (if not more) than their customers and their customers are not patients. They’re alignment to shareholders and customers is purely economic. We’ve supported this model to the tune of over 400 ISV’s that now offer “certified” EHR software to some customers ‒ almost entirely in proprietary formats based on each vendor’s commercial interests.

All of which begs the question. Absent any National Standards often used in other industries as a way to effectively neutralize all of these competing interests ‒ who is truly to blame? Congress for actively “blocking” the development of National Standards ‒ or ONC for lacking the technical ability to police an entire industry for “information blocking?”

But that’s also a serious charge. How is Congress actually ‘blocking’ the development of National Standards in healthcare? For insight into that exact dilemma ‒ it’s important to link the release of ONC’s report with another headline from last week.

Congress Continues to Block Nationwide Unique Patient Identifier

There’s that word again ‒ ‘block’ ‒ only this time aimed squarely at Congress ‒ not the EHR ISV community. According to the article, the resulting damage from this one ‘block’ has serious and direct patient consequences.

According to a survey of healthcare CIOs conducted by the College of Healthcare Information Management Executives, error rates due to patient mismatching averaged eight percent and ranged up to 20 percent. In addition, 19 percent of the respondents indicated that their hospitals had experienced an adverse event during the course of the year due to a patient information mismatch.

The history to this one Congressional ‘block’ goes back to the passage of HIPAA and I wrote about that history as a part of that 5‒part series on interoperability just over one year ago.

Who Stole U.S. Healthcare Interop?

Long forgotten is a similar dilemma in a vastly different industry ‒ motor vehicle manufacturing. For decades, car companies issued their own vehicle identification number. The resulting mess made it virtually impossible for consumers (let alone law enforcement) to tell if a car they were about to buy had been stolen, was a lemon, part of a manufacturer recall or if it had serious damage (manmade or otherwise) somewhere in its history.

A vehicle identification number, commonly abbreviated to VIN, is a unique code including a serial number, used by the automotive industry to identify individual motor vehicles, towed vehicles, motorcycles, scooters and mopeds as defined in ISO 3833. VINs were first used in 1954. From 1954 to 1981, there was no accepted standard for these numbers, so different manufacturers used different formats. In 1981, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration of the United States standardized the format.It required all over-the-road-vehicles sold to contain a 17-character VIN. VIN [Wikipedia]

Today, that VIN is stamped on every major part of every vehicle manufactured in a way that makes it easy for consumers and law enforcement to check on the status of any car (or car part) easily and quickly ‒ nationally.

So, there’s really no mystery to this Kabuki dance between ONC, ISV’s and Congress. ONC is firmly stuck between enormous commercial interests and a clearly recalcitrant Congress to simply authorize the development of any National Standard for healthcare IT (either NPI or more broadly for data interoperability). ISV’s are, of course, competing aggressively for revenue and market share in any way they can. Patients are the collateral damage in these competing interests.

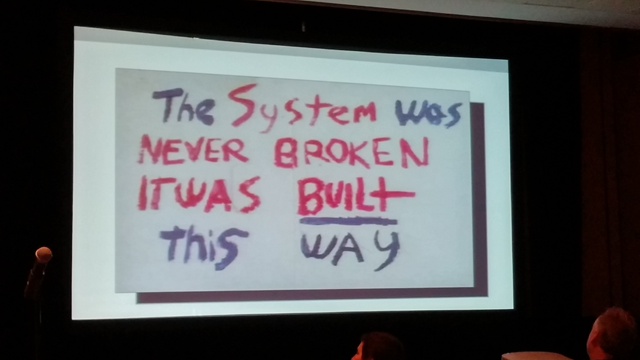

It’s painful to watch and it’s painful to realize the complete and utter disregard by all for basic patient safety ‒ but that is the healthcare system we have built. No, it’s not broken ‒ it’s just been optimized for revenue and profits ‒ not safety and quality. Congress simply refuses to reign in the commercial interests of the ISV’s and ONC is simply an effective buffer to hide their clear ‒ financially motivated ‒ reluctance.

Everyone’s well meaning, of course. Everyone’s doing “the best they can”, but it’s very much like the quote from the recent Ken Burns biography of cancer. With a little substitution we can easily apply the title of the second installment of that epic series directly to the healthcare interoperability dilemma.

The important thing is that the

viralNational Patient ID theory was not wrong. TheenvironmentalMeaningful Use theory was not wrong. ThehereditaryVendor API theory was not wrong – they were just insufficient. It was like the blind man and the elephant. They were catching parts of the whole and then all of sudden – if you stepped back – you saw the whole elephant. Siddhartha Mukherjee, MD ‒ Top 10 Quotes From the Ken Burns Documentary: ‘Emperor of All Maladies’

Unlike the war on cancer, we haven’t seen ‒ nor do we appear to be looking for ‒ the whole elephant.

This article first appeared on HIT Consultant