On October 3rd of last year, President Trump signed a Executive Order (EO) #13890 with sweeping implications for how Medicare is priced and, by extension, how much the government winds up spending annually on Medicare. In fact, the whole EO signing ceremony is really designed to satisfy the optics of legislative action where none is legally permissible. Congress still holds the purse strings, so any increases to Medicare spending would obviously require congressional approval. Executive Orders have all the pomp and appearance of real legislation – including the requisite chorus of fist pumps and smiling faces – but they aren’t.

Congress keeps a pretty firm hand on the reins when it comes to Medicare spending. I don’t know what legal authority the administration hopes to draw on, especially if what it wants to do is increase the prices it pays for services through traditional Medicare.

Nicholas Bagley, Law Professor – University of Michigan

Independent of Trump’s legal authority through executive decree (I’m not an attorney), the actual wording of the EO appears to be hastily written and fraught with ambiguity around intent, but then that also makes perfect sense when speed to the signing ceremony is the top priority. Here’s the wording in the EO that I’m referencing.

Section 3(b): The Secretary, in consultation with the Chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers, shall submit to the President, through the Assistants to the President for Domestic and Economic Policy, a report within 180 days from the date of this order that identifies approaches to modify Medicare FFS payments to more closely reflect the prices paid for services in MA and the commercial insurance market, to encourage more robust price competition, and otherwise to inject market pricing into Medicare FFS reimbursement.

Long sentencing aside, HHS Secretary Alex Azar is to submit a report within 180 days “that identifies approaches to modify Medicare Fee-For-Service (FFS) payments to more closely reflect the prices paid for services in MA and the commercial insurance market.” Taken literally, that’s a huge price increase – and could easily bankrupt the Medicare Trust Funds (yes, there’s more than one) in a matter of months. In fact, many argue that our current healthcare cost crisis stems from inelastic pricing in the commercial insurance market.

The U.S. spends twice as much per person on health care as other high-income countries. The reason we spend more is because of higher prices, and those higher prices are mainly in the commercial insurance market. When it comes to keeping health care prices down, it’s hard to see how making Medicare look more like the private insurance market would be progress.

Larry Levitt, Executive Vice President for Health Policy, Kaiser Family Foundation

Granted, it’s relatively easy to be sweeping with reform ideas when healthcare pricing is so large and opaque, right? I mean who even knows what pricing looks like in “the commercial insurance market?” We all know it’s highly variable, but that’s not very mathematical, so how can anyone really score the total cost if commercial pricing is so mysterious? In the phrase made famous by Matt Damon in the movie The Martian, “let’s do the math.”

Using claims data from about 1,600 hospitals across 25 states, RAND Health Care published a study earlier this year suggesting that the national average for commercial inpatient pricing was +241% of Medicare pricing (2017). Here’s the actual quote:

Relative prices, including all hospitals and states in the analysis, rose from 236 percent of Medicare prices in 2015 to 241 percent of Medicare prices in 2017.

RAND Health Care Study: Price Paid to Hospitals by Private Health Plans Are High Relative to Medicare and Vary Widely

While RAND didn’t extend their analysis to include traditional (non-surgical) outpatient pricing – it’s reasonable to assume that commercial rates for outpatient prices are on par with inpatient prices – but let’s err on the side of caution and use +159% of Medicare for outpatient commercial pricing. Combining these two percentages equals a blended rate of +200%. At the simplest level, the RAND study suggests that healthcare pricing through commercial insurance is roughly double what Medicare is priced at. That’s the first variable.

The second variable is annual Medicare spending. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) projects that Medicare will spend about $857 billion in 2020 – but let’s round down for simplicity to $850 billion. Using the blended rate from above (2X), a rough calculation suggests that by using commercial pricing, Medicare will spend about $1.7 trillion in 2020 – or about $33 billion per week.

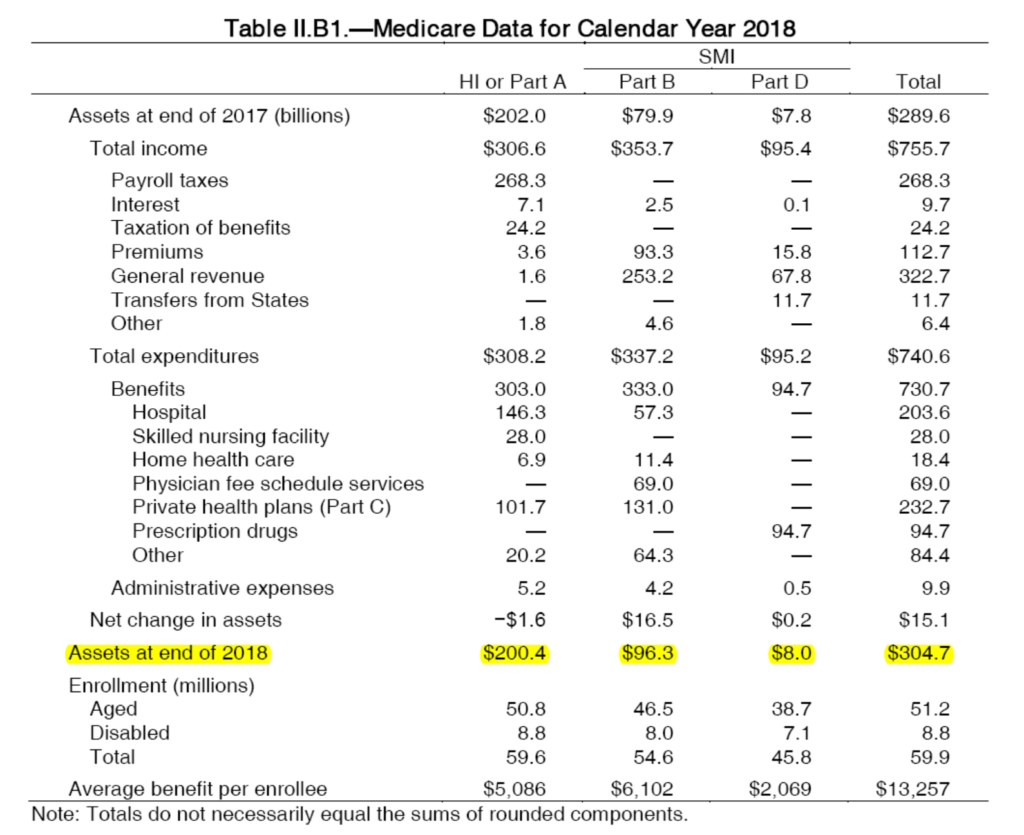

Our final variable is the balance in the Medicare Trust Fund. In April of this year, the Board of Trustees of the Medicare Trust Funds released their annual report indicating that the balance in the Medicare Trust Funds at the end of 2018 was about $305 billion.

BOARD OF TRUSTEES OF THE FEDERAL HOSPITAL INSURANCE

AND FEDERAL SUPPLEMENTAL MEDICAL INSURANCE TRUST FUND

Keeping in mind that Medicare is reasonably funded for the 2020 forecast ($857 billion), let’s also say that doubling Medicare pricing only draws down from the Trust Funds by 50% per year (or roughly $16 billion per week instead of the full $33 billion per week). At an increased spending rate of $16 billion per week, the Medicare Trust Funds (about $305 billion) would be depleted in a little over nineteen weeks – or less than 5 months. If, in fact, we use the full $33 billion per week price increase, the Trust Funds would reach $0 in just over 9 weeks.

Granted, none of this is detailed financial forecasting (and I’m not an accountant) so I do have to emphasize that this is all back-of-the-envelope math, but it does expose at least some of the financial risk of moving Medicare to commercial pricing. Frankly, I don’t think this was the original intent, but by adding the phrase “… and the commercial insurance market” it’s really impossible to decipher just what the real intent was. At least until we see the detailed report Trump called for (April 2020), we’ll just have to hope the intent isn’t to bankrupt the Medicare Trust Funds.

______________________

NB: This post first appeared on Forbes in October of 2019 and has been lightly edited.