If you don’t know history, then you don’t know anything. You are a leaf that doesn’t know it is part of a tree. Michael Crichton

In most of Europe, mass transit is so affordable and ubiquitous it’s largely assumed. Clearly the economics play an important role because gas is comparatively expensive. Most of Europe is over $5 a gallon today – and Italy and the Netherlands are both over $6. As of April 11, Norway is $6.78 and Hong Kong is $6.85.

The economics to public transportation here in the U.S. tilts heavily toward an entire economy (social and financial) built around vehicle ownership. Comparatively low fuel prices help, but the furor over the lack of European style affordable (and cohesive) mass transit usually starts when gas prices spike over an arbitrary but noticeable index. $5 could well be that index.

It’s easy to understand the original logic of American suburbia because oceans of land were cheaper outside of the city, less congested, and more amenable to raising families, back-yard activities, parks, and shopping malls. As concentric circles, suburbia grew further and further away from city centers, requiring longer distances and commutes using personal transportation.

The historic result of this is that many metropolitan cities in the U.S. continue to struggle with affordable mass transit at scale. Just this year both Washington, D.C. and San Francisco hit major roadblocks with key elements of their metro transit systems.

All of which brings us to one system in particular known as (San Francisco) Bay Area Rapid Transit – or just BART. Like the headline quote by author Michael Crichton, the history to BART has lessons that go well beyond mass transit – and run headlong into a new generation of designers and engineers – including those in software and healthcare IT.

But first a little of that history.

The “Pacific Railroad Acts” were a series of Congressional acts that actively promoted the construction of a transcontinental railroad (the “Pacific Railroad”) in the United States. This was largely accomplished through the issuance of government bonds and large land grants to the big railroad companies of that time.

The first “act” was the Pacific Railroad Act of 1862 – which had an incredibly long name:

An Act to aid in the Construction of a Railroad and Telegraph Line from the Missouri River to the Pacific Ocean, and to secure to the Government the Use of the same for Postal, Military and Other Purposes.

Buried in the actual legislation – from an era when there was a fully functional government – is this gold nugget.

The track upon the entire line of railroad and branches shall be of uniform width, to be determined by the President of the United States, so that, when completed, cars can be run from the Missouri River to the Pacific Coast. 37th Congress – 2nd Session – Section 12 – 2nd Sentence (page 495)

Even then, it didn’t take engineering arguments to understand the value and benefit of a standard – and mandated – track gauge. With some minor exceptions (like rapid transit systems and streetcars) the majority of railroad gauges in the U.S. (and North America) remain at 4 feet, 8.5 inches wide to this day.

Wikipedia summarized both the obvious and extended benefits of this reasonably well.

As well as the usual reasons for having one gauge (i.e. being able to operate through trains without transfer arrangements), the North American continent-wide system of freight car interchange with rolling stock having the same standard gauge, couplings, and air brakes meant that individual companies could minimize their rolling stock requirements by borrowing from other companies.

It’s not just passenger convenience – it’s the sizable economics of freight transit by rail.

But San Francisco has always been a tad different – and that included the heady engineering climate during which BART was originally designed and built. Leading the race to the moon, NASA was the engineering envy of the world and large new projects – like BART – were specifically intended to be both “space-aged” and “state-of-the-art.” Like a line out of the movie Jurassic Park (novel and screenplay by Michael Crichton) they “spared no expense” when it came to design thinking.

Back when BART was created, (the designers) were absolutely determined to establish a new product, and they intended to export it around the world. They may have gotten a little ahead of themselves using new technology. Although it worked, it was extremely complex for the time period, and they never did export the equipment because it was so difficult for other countries to install and maintain. —Rod Diridon, Emeritus Executive Director of the Mineta Transportation Institute in San Jose (as quoted in the San Jose Mercury News – March 25, 2016).

Almost everything about BART was new – and different – starting with a critical and foundational component; a unique track gauge of 5 feet 6 inches. Since BART was designed to be standalone (not connected to other rail systems), the unique track gauge was considered a bold and compelling design feature at the time, but like all things engineering, that fateful decision led to a cascading string of other requirements – including custom-made wheel sets, brake assemblies and track repair vehicles – all to match the unique track gauge.

Yet another design “innovation” was a flat-edge rail that requires more maintenance and is actually noisier. Custom aluminum wheels (to reduce weight) with stainless steel “tires” (to reduce noise) were added with no real thought as to long-term maintenance, repair, or replacement.

The 1,000-volt traction power system was also cutting-edge – and unique. Even some of the small electrical components (which are breaking now with some frequency) are expensive and can “usually take 22 weeks to order.” Earlier this year (after a significant service interruption) BART announced the need to buy 100 “thyristors” at a cost of $1,000 each.

Thyristors are the small group of white rings just above and to the right-of-center in this picture

At the very heart of this modern marvel was a computer system that was “state-of-the-art” when it first opened to public travel – in 1972. Today, even relatively minor updates to the software can cause system wide crashes for entirely unknown reasons. Some of BART’s maintenance software still runs on Windows 3.1 (presumably on a secure network). When a system wide software crash does happen, it is literally back to manual switching along the 104-mile system.

Without computers controlling the system’s 400 track switches on the main line, operators had to get out and physically change those switches to ensure that their trains remained on the proper tracks, with each change taking from five to 10 minutes. At some of the more complicated switch points, special crews were sent out to work them. It was all hands on deck. If you were trained and authorized to crank a switch, you were out there. Alicia Trost – BART Spokeswoman (SFGate 11/2013)

At the time of its launch, BART was engineered to accommodate what was considered (at the time) to be a large number of passengers – 100,000 each week. Today it handles over 400,000 – per day – and is the fifth-busiest rapid transit system in the U.S. The enormous stress on the system through the years has caused some to suggest that BART is effectively past “end-of-life” (in the mechanical engineering sense) and on “life support.”

Whether BART is truly on “life support” or not is almost immaterial because there’s a November ballot initiative to raise about $4 billion – just to keep BART running mechanically. It will remain a constant engineering battle – and enormous cost – for as long as the track is stuck at its proprietary 5-foot 6-inch width.

What does any of this have to do with healthcare? When you consider that industry standards around digital data are the modern equivalent to railroad track gauges – it has everything to do with software engineering for healthcare.

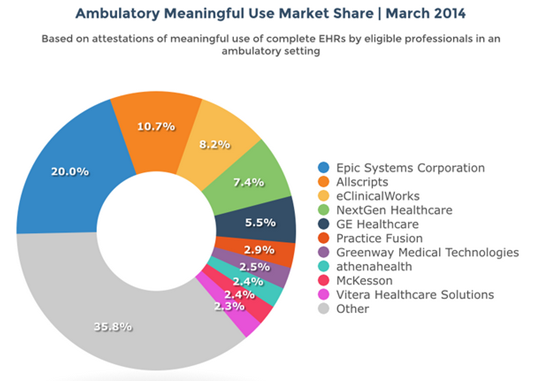

Considered enterprise software, large EHR systems in hospitals tend to drive the market and fortunately, over 90% of the inpatient EHR market is divided among 10 sizable vendors.

But unlike the lone BART, there are about 5,600 hospitals in the U.S. In the analog paper world – each hospital was logically an island. All of which is an enormous financial benefit to the software vendors because all the proprietary and unique software requires constant patching, maintenance, and updating.Unfortunately, this gang of 10 is in the business of selling heavily customized software – to accommodate the “unique” and “proprietary” needs of each and every hospital they sell to. Everything from initial design to implementation, training, and maintenance is effectively custom built to each hospital installation. Each hospital installation is effectively a BART, and like BART – standalone. The lack of a data standard for communicating between hospitals is exactly like having a unique track gauge – for each and every hospital.

In hindsight, it’s hard to understand this engineering hubris – for both BART and non-standard EHR software – except that they share roots in the same commercial logic of revenue and profits. Remember, BART was going to build and sell mass-transit systems to other municipalities and countries.

This profit-centric logic has spawned an entire healthcare IT industry that continues to enjoy a healthy and lucrative future – and one that we’re all paying for in a myriad of ways that are both economic and safety related. What we don’t have (lacking a functioning government) are the data standards for patient safety and quality. In effect, our entire healthcare system (including healthcare IT) has been optimized for revenue and profits.

Just this week, ECRI issued their list of Top Ten Patient Safety Concerns for Healthcare Organizations.

Since 2009, when ECRI Institute PSO began collecting patient safety events, we and our partner PSOs have received more than 1.2 million event reports. That means that the 10 patient safety concerns on this list are very real. They are causing harm—often serious harm—to real people.

My only real surprise is that on their top 10 list, patient identification didn’t make #1 – it came in at #2.

During routine reviews of reported events, ECRI Institute analysts discovered that patient identification issues were frequent. And serious consequences were evident.

Is there a solution? Sure, in much the same way that as a country, we determined that if you want to ride a train from Missouri to the Pacific Coast, everyone benefits by having a standard track gauge. Competing commercial interests have no incentive to voluntarily create – let alone agree to one for data in healthcare – and especially one that puts their revenue at risk. Put bluntly, the gang of 10 all risk losing big chunks of revenue if health data is standardized like a track gauge.

Absent a mandated data standard everything done today is just like keeping BART afloat – at huge expense. It will always be the most expensive kind of engineering work because it’s all made-to-order, custom-built and supported – and switching costs are astronomical. BART officially opened in 1972, but the foundational thinking – how to maximize revenue and profits – is very much alive and well in healthcare IT to this day.

History often repeats itself – at sparing no expense.

This article first appeared in Health Standards (April 2016)