This article was originally written in 2015 and links were updated in 2021

The headline couldn’t have been more focused and directed against a single EHR software vendor. It screamed in bold, capital letters ‒ EPIC FAIL ‒ but then for some reason, backpedaled with the subheading.

Digitizing America’s medical records was supposed to help patients and save money. Why hasn’t that happened?

Since it’s original publication date (October 2015), the headline has been changed and now reads:

We’ve Spent Billions to Fix Our Medical Records, and They’re Still a Mess. Here’s Why.

It’s a reasonable question for the industry, of course, which is the way the subheading phrases it, but that’s not the responsibility of a single commercial software vendor, regardless of their size or corporate structure.

To date, the MotherJones article by Patrick Caldwell has generated over 260 comments, 1,100 tweets and 3,400 shares on Facebook. Most of the comments are supportive of the Epic Fail premise, but the primary argument ‒ as stated in the 4th paragraph of the 2,300+ word essay ‒ is technically wrong.

But instead of ushering in a new age of secure and easily accessible medical files, Epic has helped create a fragmented system that leaves doctors unable to trade information across practices or hospitals.

Epic has certainly contributed to the challenges of sharing patient data ‒ but to blame them for lack of interop is about the same as blaming Apple for fragmenting the mobile world with iOS. In a nutshell, software is only designed, marketed and successfully sold when it does what customers want. Nowhere is that more true than on the expensive enterprise side of software manufacturing. It only sells to people willing (and able) to buy it ‒ often by the billions of dollars.

To be clear ‒ I’m not an Epic fan anymore than I’m an Apple fan ‒ but there are parallels. The biggest, easiest distinction, of course, is that Apple creates the whole consumers experience (hardware and software), and Epic is exclusive to enterprise software only.

By about paragraph 11 we finally get to the argument that’s at the heart of the whole HITECH Act ‒ which includes Epic and about 400 other software vendors that manufacture and sell electronic health record software.

As it stands, she [Julia Adler-Milstein, a University of Michigan researcher who studies health care IT] says, using Epic is easier than trying to piece together better options from various software vendors. On top of that, Epic will tailor each installation on-site to a customer’s specific needs. What it doesn’t have—and ditto systems created by competitors Cerner and Meditech, the other bigwigs in EHR—is a framework to connect to other facilities using competing EHR systems.

It’s perfect staging for the appearance in the next paragraph of healthcare’s word of the year ‒ interoperability. For such a lengthy article ‒ it’s surprising that the interop word only appears about 5 times, but that’s really the point of the whole piece ‒ and the biggest charge against Epic.

Without defending Epic, here are some “interop” statistics that Epic President Car Dvorak gave to ONC’s Health IT Policy Committee last year ‒ under oath.

Epic has strong support for “standard HL7 traditional interfaces,” as well as other transaction types such as NCPDP and ANSI X12, enabling “about 20 billion data transactions per year, over 12,000 different interfaces across our 320 customers, to about 600 other vendor systems ‒ including 88 public health agencies, 18 research societies, 51 immunization registries across 46 states and 17 research registries. As for meaningful use, specifically we support the Direct protocol, which is reasonable for planned transitions of care. That “is clearly better than nothing,” he said, but it’s just as clearly inadequate for unplanned transitions such as ED visits. For those, “we support Healtheway exchange standards ‒ the Connect or NwHIN standards; we think both are vital for solving interoperability in the country,” said Dvorak. More generally, he pointed out that Epic’s Care Everywhere technology enables the exchange of 480,000 consolidated clinical document architecture, or C-CDA, documents each month with products built by other vendors – and that number is on the rise: more than double the amount that changed hands as of January 2014. That exchange ecosystem “includes about 900 hospitals, 20,000 clinics, with another 85 hospitals and 3,000 clinics coming online in the coming year,” said Dvorak.

We connect to 26 other vendors systems, 21 HIEs, 29 HISPs and 28 eHealth Exchange members,” with 20 more coming online soon” he said.

Epic Defends Interoperability Bona Fides by Mike Miliard / Editor, Healthcare IT News

We should demand this type of interop accountability from all the EHR vendors. To date, I’ve only seen it from one ‒ Epic.

Also lost in any discussion is the cost by software manufacturers to actually build the gateways into competing software systems. They can do that and they often do ‒ for a fee ‒ but like every other industry, software engineers expect to be paid for their work. Sorry, but just because it’s healthcare, doesn’t entitle industry observers to “free software.”

“We have what I would call a ‘loosely-defined’ standard that’s subject to interpretation. At the end of the day, for two systems to figure out how to convert and communicate, there’s some level of manpower, hours and efforts that are required. If you’re a for-profit organization, this results in having to charge somebody for their time. There’s a cost for interoperability, and that’s where we get a lot of talk.” Mark Janiszewski ‒ EVP of Product Management for Greenway in The Vendor’s View of Interoperability ‒ Becker’s Health IT and CIO Review

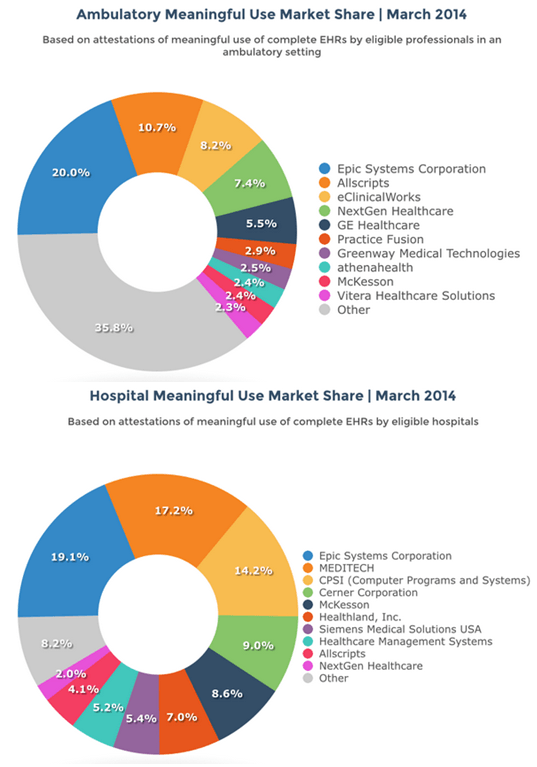

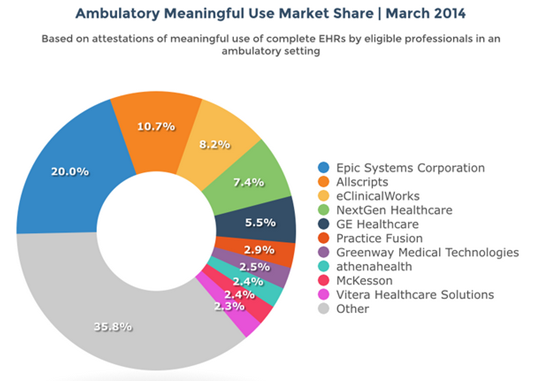

A survey in 2014 suggested that Epic owns about 20% of the inpatient market and about 20% of the ambulatory market. That’s an important distinction because the fragmented market often referenced is really the ambulatory one ‒ where there are newer entrants that tend to have relatively small percentages of the market but are among the most vocal when it comes to screaming about “interoperability.” It’s also easy to make that noise and attract free publicity, but it doesn’t solve any problems.

Here are two charts highlighting that exact point from a firm called Software Advice. They published their EHR Meaningful Use Market Share for 2014 last year and included two helpful charts. There are other studies, of course, but most of the really current ones are by firms that charge big bucks and then heavily restrict public disclosure.

For our purposes, however, it doesn’t matter that much because the market just isn’t that volatile ‒ especially at the top. Here’s the Software Advice chart for the ambulatory market.

Software Advice was quick to highlight the visibly obvious here.

What’s surprising is how fragmented the market continues to be: five of the market’s top 10 vendors boast a market share of less than 3 percent each, and nearly 40 percent of the market uses an EHR from a vendor that falls outside of the top 10.

Here’s the Software Advice chart for the inpatient market (Hospitals) that MotherJones could also have included ‒ but elected not to.

Software Advice was equally quick to highlight the obvious here as well (bold emphasis mine).

When it comes to inpatient hospital attestations, the biggest vendors show greater market dominance: the top 10 account for over 90 percent of the market, while the top three alone account for over half of it.

While it may be popular, the case against any single vendor for the industries lack of interoperability is just technically wrong. The only real mistake here ‒ and it’s a big one ‒ was the original legislation called HITECH ‒ which paid for EHR adoption, but didn’t insist on standards for sharing information. Commercial software companies aren’t responsible for Government failures and by comparison, no one looks at the sizable lead that Android has in the mobile world and blames Google for failing to “interoperate” with Apple.

Commercial software in the healthcare industry isn’t automagically different than commercial software in other industries except that our Government did pay handsomely (to the tune of almost $30 billion) to accelerate the adoption of EHR software. If, as a part of the HITECH Act, the Government had wanted “interoperability,” it could have ‒ and should have mandated it. MotherJones finally acknowledges this deep in the article.

Epic is not the only barrier to a seamless medical records system. Thanks to legislative maneuvering by former Rep. Ron Paul (R-Texas) in 1999, the federal government can’t fund any sort of system with unique health care identification numbers. (Paul saw individual medical IDs as further creep of Big Brother). Social Security numbers aren’t a good fill-in; they’re not on insurance cards, and in April Obama signed a bill that will strike them from Medicare cards in order to reduce identity theft.

Large and influential healthcare IT organizations like CHIME and HIMSS have all recognized the enormous handicap of trying to build interoperability without this critical component. They are also joined by influential CIO’s like Michael Blum at UCSF who called the Congressional ban on establishing a universal patient identifier “the biggest single failure in the history of health IT legislation.” [page 189 of The Digital Doctor by Robert Wachter, MD]

Everyone’s entitled to an opinion of course and it’s certainly popular to blame Epic for all that ails in getting EHR software to share patient information, but almost all the reasons for the blame revolve around safety and quality. The healthcare system we have has been optimized for revenue and profits ‒ not safety and quality ‒ so neither the system or Epic is “broken.” It was actually designed this way and we need to change the design. Hating Epic Systems Corporation may be popular ‒ and it may even feel good ‒ but it’s totally misdirected and won’t change one byte of their software.